In a recent Channel News Asia program erstwhile Indonesian Trade Minister Mari Pangestu expressed concern about “the goods that were originally supposed to go to the US will have to find new markets”.

Indonesia is not the only country to be concerned about this. After all China is about scale, competition, efficiency, innovation and speed to market. In the same program Professor Wang Yiwei of Remin University, said that China can produce “everything from matches to rockets” and if China produces anything, its “price will become as cheap as cabbage”.

It is difficult to provide a definitive answer to Mari Pangestu’s concern. No one really knows how America’s trade war against the world is going to play out, partly because economies are so interconnected but more so because of the unpredictability of the American President. If the desired effects don’t play out, frustration will likely lead to more rash behaviour.

In the short term, Chinese exporters will have to rely on the domestic market, find new export markets and some will have to fold.

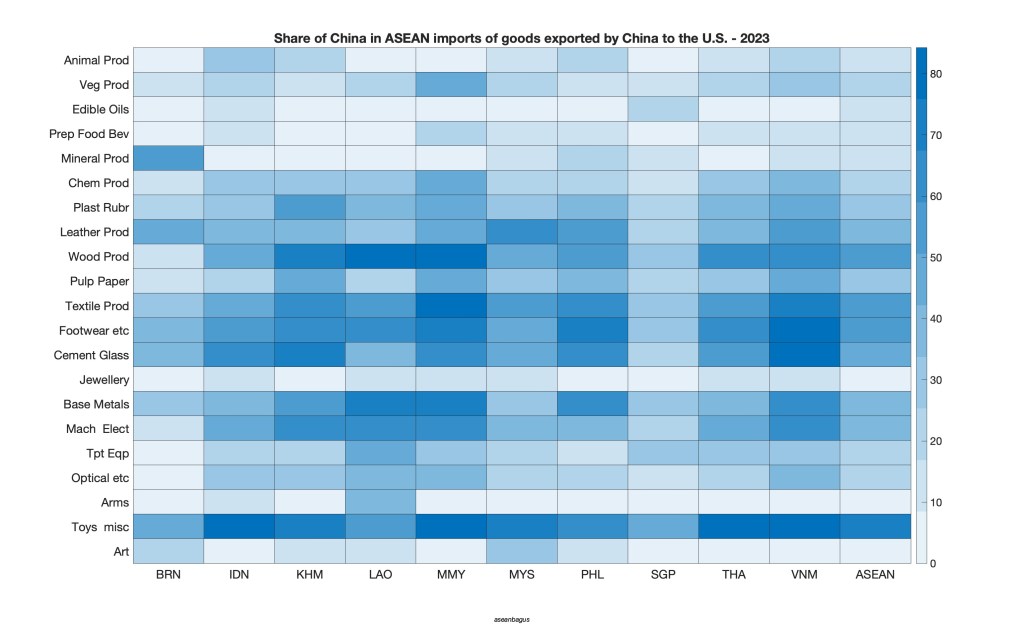

Surely some of the goods that were intended for sale in the U.S. may find their way to Indonesia, but Indonesia is unlikely to be amongst the top destinations. In 2023, goods that were exported by China to the U.S. (excluding those which are exempt from tariffs) were also exported to 207 other countries. Indonesia ranked 15th as a destination (using value of imports). Vietnam was in 4th place and Thailand in 11th. If the focus is limited to consumer goods (as defined by UNCTAD), Indonesia drops to 22nd place. As the following figure shows, China already has a large market share in many segments. How many more toys can Indonesian children buy?

Mari Pangestu did not ask the opposite question: Can Indonesia export goods to China that the latter previously purchased from the U.S.? In 2023, China imported the same goods it imported from the U.S. from 203 other countries. On this list, Vietnam ranked 6th and Indonesia ranked 8th. If the focus is limited to consumer goods, Vietnam ranked 5th and Indonesia 11th. This is the potential benefit side of the equation.

And what if Indonesia’s ‘hostage negotiations’ with the country which does not honour its existing obligations don’t work out? In 2023, Indonesia exported the same products that it exported to the U.S., to 203 other countries. Of the next 20 destinations, 14 are in Asia (including West Asia). Going further down the list shows that Indonesia is already well connected to the to the global majority in Africa and Latin America. These are the growing regions of the world with which Indonesia can strengthen and expand its economic links.

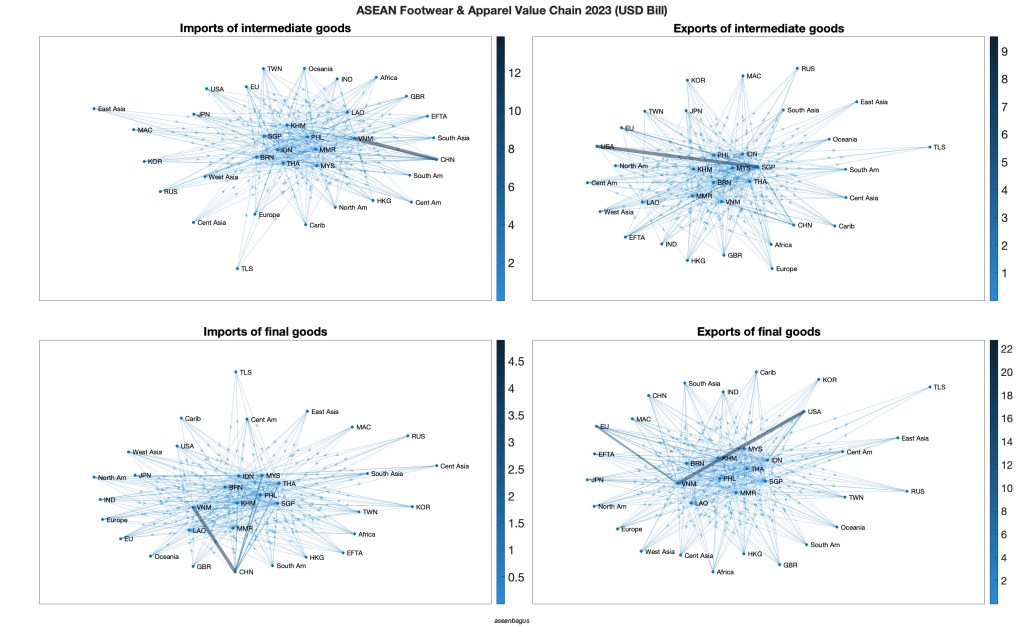

Trade diversion is a short-term issue. The bigger and more complicated issue is how the tariffs on Chinese goods and possibly on other Asian economies will impact value chains. The interdependence is evident from the following figure and similar figures can be generated for the auto and electronics supply chains. All show that while Indonesia may not be the biggest participant in value terms, it is a highly connected participant.

Rather than worrying about trade diversion, Indonesia and other ASEAN countries need to develop a national economic strategy which incorporates a ‘U.S. plus x’ approach. Given the previous eight-year history of the imposition of tariffs and export controls by the U.S. on China, protectionism and blaming others should be treated as both structural and a one-way street. There is no turning back.

Sources

Trade data are from the BACI balanced trade database (6-digit HS 2007 for the year 2023 for the first figure (heat map) and 6-digit HS 2012 for the year 2023 for the second figure).

The list of consumer goods (UNCTAD) and the list of final and intermediate goods for the footwear and apparel value chain are both available on the WITS website (Reference Data).

Exclusion List (USCBP)

First published on Substack on April 30, 2025.

Leave a comment