About two months ago, India’s Commerce Minister Mr. Piyush Goyal ruffled some feathers at home and in ASEAN. According to the Straits Times, at an event in London he said:

There was a point of time 15 years ago when we were more focused on doing trade agreements with countries who were our competitors … So, if I do an ASEAN agreement with Indonesia and Malaysia and Vietnam and Thailand and Cambodia and Laos… it really is silly because I am opening up my market to my competitors

It was better, he said, to do deals with complementary economies such as those of the UK or Australia, with whom the Indian has recently signed free trade agreements (FTAs). And negotiations are apparently underway with the EU, EFTA, Chile and Peru. Nothing wrong with that logic, and what he calls “silly”, is doing FTAs with competitors, which was done by the previous Congress government.

But here is the insult. Referring to ASEAN countries, he said:

Many of whom have now become the B team of China … So effectively and indirectly, I have opened up my market for goods that find their way from China into India.

And his timing was no good either as at the time, because these comments were made when Indian officials were in ASEAN for discussions.

Fifteen years ago, the insults were going in the opposite direction and while they were expressed in private, they were exposed by Wikileaks in 2010. Then Singaporean diplomat Professor Tommy Koh described his “stupid Indian friends” as “half in, half out” of ASEAN.

The ASEAN-India trade relationship is an important one. ASEAN as a group was the second most important (after the U.S.) export destination for India in 2023. India ranked seventh as an export destination for ASEAN. The UK was the 5th most important destination for Indian exports, and Australia at 14th was behind Singapore – 9th and Indonesia – 13th. Countries such as Peru and Chile, ranked below 50th.

To examine complementarity, I calculate the World Bank’s Trade Complementarity Index (higher value indicates higher complementarity) for 2023 with India as the exporter. The TCI for ASEAN was roughly 42, Indonesia and Australia: 46, Malaysia and Myanmar: 41, Philippines: 39 and Cambodia, Singapore and U.K. at roughly 37. The data show that the Minister’s complementarity argument fails – there is nothing special about either the U.K. or Australia. In fact, ASEAN has an advantage over the U.K. and even the EU. It has much better growth prospects a bigger market size and better demographics. The EU and the U.K. economies are stagnant at best and have ageing populations.

More importantly, ASEAN offers not scale, but diversity or variety. Countries are at different stages of economic development, and this offers more opportunities for complementarity and for peer-competition and peer-learning across sectors. Of course, given ASEAN’s openness, Indian firms will also encounter third-country competitors in ASEAN member states, which is a good way to both gauge and enhance competitiveness.

What is really bothering the Indian minister, is the trade imbalance. India has had a negative trade balance with ASEAN for many years, and it has only grown over the years. In 2023 it had a negative trade balance not just with ASEAN as a group, but with every ASEAN member state. According to the Straits Times, in financial year 2023-24, India’s total trade with ASEAN was roughly 120 billion USD and India’s trade deficit was about 38 billion USD. Trade imbalances reflect country capabilities and needs. Putting price and quality aside, which are very important, if India needs palm oil it has to buy it from ASEAN and if ASEAN wants a lot of jewelry, it may buy it from India – the trade balance will be where it will be. But Indians assert that China does not compete ‘fairly’ and that some Chinese goods are trans-shipped to India through ASEAN. Some Indian producers suggest that they face non-tariff barriers (NTBs) in ASEAN, but there is academic research to indicate that any negative effects of NTBs are outweighed by the positive impacts of openness and economic growth.

If India can show that China is using unfair trade practices, like many ASEAN countries it can impose countervailing duties on those products. Recently, Malaysia, Thailand and Vietnam have imposed duties on Chinese steel products and Indonesia is planning on imposing duties on textiles and footwear. Avoiding China is not the answer and India is the only large economy that is not part of a regional trade arrangement. It should encourage more foreign direct investment from both ASEAN and China to create manufacturing jobs, improve skills and increase domestic competition. In any case India depends on China for a lot of intermediate goods in sectors such as solar, textiles, electronics and pharmaceuticals. Forming joint ventures to undertake domestic production will assist India’s transformation. Like China, India needs to transform at scale and at low cost.

It is unlikely however that Indian attitudes will change. At the Economic Times World Leaders Forum on August 22, 2025, Mr. Goyal expressed concerns about both the ASEAN trade deal and RCEP. On the ASEAN trade deal, he said that domestic industry gives him negative feedback suggesting that the opening up was asymmetric, in other words India gave more concessions than ASEAN. He also said that RCEP would have been the “death knell” of Indian industry as it would have effectively been an FTA between China and India and again an over whelming majority of Indian farmers and Indian industry were against the trade deal. Industry should be consulted in formulating trade policy, but the interests of domestic business should not drive trade policy, since all industries in all countries prefer protection to competition. In the case of the highly concentrated industrial sector, most of the benefits of protection go to the large Indian conglomerates. Indian industry needs more competition, not less. If India cannot use Competition Law to increase domestic competition or use other means to facilitate the entry of new firms, then the only other alternative is to subject firms to foreign competition. India definitely does not want to compete with China, and possibly not with ASEAN because it knows it cannot compete. In fact, I suspect India does not want to trade, it wants to export, and it wants access to foreign capital and technology. Unfortunately, the world does not work like that.

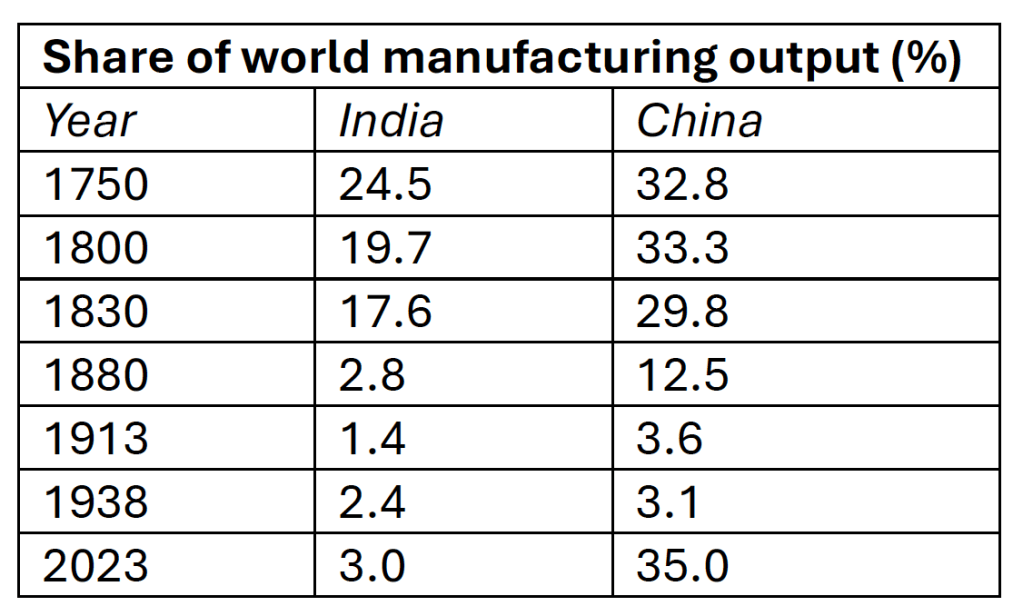

Meanwhile, China has achieved its past manufacturing glory and India has not, it is still stuck in the colonial period.

In the First Opium War 1839-42, China was fighting the British. The signing of the Nanjing Treaty in 1842 marked the beginning of the ‘century of national humiliation’ for China.

The Charter Act of 1813 ended the East India Company’s monopoly and opened up India to all British merchants. India’s de-industrialization was due to various factors including the industrial revolution in Britain and discriminatory tariffs – low tariffs on British goods imported into India and high tariffs on Indian exports to Britain. Very similar to what India faces now with the Americans.

Regardless of whom India signs FTAs with, the solutions to India’s competitiveness problems lie in domestic policy and not trade policy. Now that the sugar high from drinking too much American Kool-Aid over the past couple of years has subsided, India needs to devise a realistic national economic strategy, in cooperation with state governments and get down to the hard and long slog of building prosperity. India has a lot of structural problems it needs to fix before it can grow at the rates that are required for it to achieve its ambitions.

India talks about a demographic dividend, but obtaining the ‘dividend’ requires eradicating child malnutrition. According to 5th National Family Health Survey of India conducted in 2019-21 child stunting was at 35.5%, wasting at 19.3% and the prevalence of underweight children at 32.1%. Wasting is an acute condition, but it can be reversed. Stunting is chronic (long-term undernutrition) and leads to irreversible physical and cognitive issues. This is mainly due to poverty, but other socio-economic variables also matter. A recent study found that children from the poorest households in India were 85.7% more likely to be stunted than those from affluent households. So, if roughly one-third of the children are stunted what is their quality of life going to be as they become adults and will they become productive members of society?

The 2024-25 Economic Survey of India states that the percentage of the workforce (15 years and over) employed in services declined from 31.1% to 29.7% over the five-year period 2017-18 to 2023-24. The share of the workforce employed in manufacturing also declined from 12.1% to 11.4% and while that in agriculture increased from 44.1% to 46.1% over the same five-year period. Regardless of the extent of international trade, the process of economic development is characterized by structural transformation. Productivity in agriculture increases and the surplus labour is employed in a growing manufacturing sector. So, employment moves from primary to tertiary sectors or from agriculture to manufacturing to services. The Indian data show stagnation at best and possibly reversal.

An overwhelming majority of Indian workers have low educational attainment and low skills. In 2023-24, 90.2% of the workforce had 13 (finished high school) or fewer years of education, as a result 88.2% of the workforce was classified as having elementary skills (22.4%) or being semi-skilled (65.8%). The skill level is reflected in the wages, with only 4.2% of the workforce earning between roughly USD 9000 to USD 4500 per year and 46% earning less than USD 1150 per year. It is no wonder that Apple’s assembly operations in Tamil Nadu need to employ either Chinese or Taiwanese engineers.

The first problem can be solved by India alone, although it may be a good idea to exchange notes with the Philippines and Indonesia. They have similar problems, and President Parbowo has made child nutrition a priority. ASEAN and China can help India with low-skilled manufacturing and skills-upgrading. Singapore is already the largest foreign investor in India and the Institute of Technical Education in Singapore has a number of occupational skills development projects in Assam, Odisha and Madhya Pradesh.

If India could just solve the two problems of child malnutrition and skills, it would make great strides, otherwise Indians will have to be satisfied with a new slogan every few years: Atmanirbhar Bharat (self-reliant India) in 2020, Viksit Bharat @2047 (India’s vision to become developed nation by 2047) in 2023 and Samriddh Bharat (prosperous India) in 2025.

Sources

Indian Minister’s Remarks June 2025 – Straits Times: https://www.straitstimes.com/asia/south-asia/india-ministers-dismissal-of-asean-members-as-chinas-b-team-hits-confidence-in-trade-pact

Indian Minister at the Economic Times World Leaders Forum: https://www.youtube.com/live/pNfOvCUkheY?si=B44K67hgmhsSsizy (11:40 – 15:30)

Tommy Koh’s Remarks: https://wikileaks.org/plusd/cables/09SINGAPORE852_a.html

Historical data in table: Williamson, J.G. (2008) Globalization and the Great Divergence: Was Indian Deindustrialization after 1750 Different?

2023 data in table: Baldwin, R (2024) China is the world’s sole manufacturing superpower: A line sketch of the rise: https://cepr.org/voxeu/columns/china-worlds-sole-manufacturing-superpower-line-sketch-rise

NTMs study: – Khati, P. and C. Kim (2025) Impact of India’s Free Trade Agreement with ASEAN on Its Goods Exports: A Gravity Model Analysis https://www.mdpi.com/2227-7099/11/1/8

World Bank Trade Complementarity Index: https://wits.worldbank.org/wits/wits/witshelp/Content/Utilities/e1.trade_indicators.htm

2023 data for calculating TCI are from BACI database (HS 2017).

GDP per capita (PPP) data are from World Bank: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.PCAP.PP.KD?end=2024&start=2022

Nominal GDP and GDP growth World Bank: https://data.worldbank.org/?locations=CN-IN

Malnutrition information – Ministry of Women and Child Development: https://www.pib.gov.in/PressReleaseIframePage.aspx?PRID=1988614#:~:text=As%20per%20the%20data%20of,were%20found%20to%20be%20wasted.

Stunting study: – Douli, M and S. Sarkar (2024) Decomposing social groups differential stunting among children under five in India using nationally representative sample. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-024-78796-3

Economic Survey of India 2024-25: https://www.indiabudget.gov.in/economicsurvey/

Chinese engineers in India: https://www.scmp.com/news/asia/south-asia/article/3322937/apples-india-push-tested-foxconn-recalls-300-chinese-staff?module=perpetual_scroll_0&pgtype=article

Leave a comment